Template:Realworld Over the course of TOS and the first six Star Trek movies, numerous studio models representing the Template:ShipClass have been created (in particular, for the USS Enterprise), even more than for any other class.

Design

The sketch Gene Roddenberry and Herb Solow approved

As art director on the original series, Matt Jefferies was given the assignment to design the Enterprise itself. His only guideline was Gene Roddenberry's firm list of what he did not want to see: any rockets, jets or fire-streams. The starship was not to look like a classic, and thus dated, science-fiction rocket ship, but neither could it resemble anything that would too quickly date the design. Somewhere between the cartoons of the past and the reality of the present, Matt Jefferies was tasked with presenting a futuristic design of his own.

The theory that space could be warped - a hypothetical means of faster-than-light travel - had first been proposed by Albert Einstein in 1905. Years later, Star Trek itself would establish that Zefram Cochrane had first demonstrated warp drive in 2063. In the 1960s, however, warp drive - a delicately balanced, intricate web of chemistry, physics, mathematics and mystery - initially perplexed Matt Jefferies. He explained:

I was concerned about the design of ship that Gene told me would have 'warp' drive. I thought, 'What the hell is warp drive?' But I gathered that this ship had to have powerful engines – extremely powerful. To me, that meant that they had to be designed away from the body. Boy, I tried a lot of ideas. I wanted to stay away from the flying saucer shape. The ball or sphere, as you'll see in some of the sketches, was my idea but I ended up with the saucer, after all. Gene would come in to look over what I was doing and say, 'I don't like this,' or, 'This looks good.' If Gene liked it, he'd ask the Boss (Herb Solow) and if the Boss liked it, then I'd work on that idea for a while. [...] So I worked on it for a while, and a couple of weeks later, Herb and Gene came in. They liked a bit of this and a bit of that, and I worked on those bits. And then I came up with something I really like, so I preloaded it – used lots of color and put it in a prominent place that made it kind of stand out. And that worked! It looked better than the other sketches and Gene said, 'That one looks good!' They – and Bobby Justman, too, when he came aboard later – were a dream to work with." (Star Trek: The Original Series Sketchbook, page 62)

The design process itself, however, proved to be arduous and time-consuming. Starting from Roddenberry's ambiguous guidelines, Jefferies started out by experimenting with shapes. As he recalls: "[...] There was a lot of floundering going on because I didn't know where the hell we were going and I had to start coming up with an envelope to work inside of. I did hundreds of sketches. Gene liked a piece of this and a piece of something else, so I tried to see what I could do with the pieces." Dozens more sketches followed, experimenting with the configuration of the selected components: "My thinking was, because of the ship's speed, there had to be terrifically powerful engines. They might be dangerous to be around, so maybe we'd better put them out of the way somewhere, which would also make them what, in aviation circles, we call the QCU - quick change units - where you could easily take one off and put another on. Then for the hull, I didn't really want a saucer because of the term "flying saucer", and the best pressure vessel of course is a ball, so I started playing with that. But the bulk got in the way and the ball just didn't work. I flattened it out and I guess we wound up with a saucer!" (Star Trek: The Magazine Volume 1, Issue 10, page 25). In August 1964, the producers approved a final configuration, based on a color illustration and a small balsa wood miniature Jefferies had made, to give Roddenberry and the NBC execs a three-dimensional feel for the ship. (It is possible that this model was even used in the original title sequence of "The Cage". [1]) "When Gene and the NBC people came in - I think there were about eight of them - they did navigate to the color piece, and I said, 'Well, if you like that, how about the model,' and held it up. Gene took it by the string and immediately it flopped over, because the birch dowels were heavier! I had an awful time trying to unsell that. And, of course, when our first show hit the air and TV Guide came out, they ran a picture of the ship on the cover, upside down," Jefferies recalled further (Star Trek: The Magazine Volume 1, Issue 10, page 26). Jefferies spent the next few months designing the color scheme and refining the chosen design. Theorizing that space was too hazardous for important machinery being on the outside of the hull, Jefferies decided that the hull had to be smooth (which had the added benefit of reflecting light in subsequent shoots). He had to fight off several production team members, who wanted to keep adding detail to the surface. In the end, Jefferies spent full time - the better part of four months - designing the ship.

Notably, two of Jefferies' earlier designs would capture the imaginations of later Star Trek production team members, like Rick Sternbach, Andrew Probert, Michael Okuda and Gregory Jein. Through their fascination and persistence, these designs would eventually find their way into canon; a "ring ship" design (dismissed by Roddenberry as being too frail-looking) would become the USS Enterprise, and the ball-shaped primary hull design, which Jefferies himself dismissed, would be the foremost influence on the design of the Template:ShipClass.

Three-foot model

Final appearance of the three-foot model in "Requiem for Methuselah" |

After final approval of his design, Jefferies went on to produce a detailed set of construction blueprints - with orthographic views of the ship - and sent it off to the Howard Anderson Company, who were to build the pre-production model. (Blueprints published in Star Trek: The Original Series Sketchbook, pages 70-71, were erroneously identified as those. They are, in fact, post-April 1966 construction blueprints drawn up for AMT/Ertl's production shop for making molds for a later edition of their first Enterprise model kit, being printed on the side of the box for the modeler's reference sake.) Richard C. Datin, Jr. (who still owns a set of the original blueprints) was eventually subcontracted to build what would become known as the "three-foot" model of the Enterprise, though its actual size would be exactly thirty-three inches.

As Datin recalls: "All lettering and the logo artwork on the secondary hull were decals. The rest, I believe, were painted on, such as the hatch indications. (...) I began work on the small Enterprise on Wednesday, November 4, 1964, and completed it by November 15 for a total of 110 hours of my time. Since I did not have a large enough wood lathe to turn out the major components (the primary and secondary hulls and nacelles), I subbed this to an old-time woodworker whose name, unfortunately, escapes me. My portion of the work was assembly, painting, and decorating. The three-footer was comprised of pattern pine - a sugar pine - primarily because it was kiln dried, free of knots, and consisted of a very fine grain. It finishes well and takes paint just as good. I was able to purchase a Plexiglas dome, a ready-made item for modelers, for the bridge. The deflector dish and secondary hull front cover were fabricated from rolled brass strips and silver-soldered together, then sprayed with a gold color lacquer." (Star Trek: Communicator, No.132, 2001, page 51) The paint schemes were selected by Jefferies. [2] After review by Roddenberry, Datin did some minor revisions and delivered the model on 14 December 1964, at a total estimated cost of $600.

Although never slated for filming purposes, but rather to serve as a study model for the yet-to-be-built larger model and for public relations purposes (including well-publicized publicity shots of Shatner and Nimoy holding the model), it eventually was used as such. A time-line drawn up by David Shaw elaborated: [3]

- 4 Nov 1964 (Wednesday): Richard Datin agrees to build an approximate three foot long model based on an early set of plans which give a real world scale of 1:192 (if this had been the final drawings, this would have been the 540' version, but the proportions of this early drawing are actually different from the final plans... including the length of the model) and for the final large scale model (the plans on the page would have most likely been 1:48).

- 7 Nov 1964 (Saturday): The final construction plans are finished. These plans include the scale reference of FULL SIZE & 3" = 1'-0" TO LARGE MINIATURE.

- 8 Nov 1964 (Sunday): Richard Datin receives the plans and starts building the full size 33-inch model out of kiln-dried sugar pine.

- 15 Nov 1964 (Sunday): A little more than a week later the 33-inch model is presented to Roddenberry for approval. This may have been when the addition of exterior windows was requested (which were not part of the original design), and the model returns with Datin after the viewing.

- 8 Dec 1964 (Tuesday): Construction is started on the 11-foot model.

- 14 Dec 1964 (Monday): The 33-inch model is delivered to Roddenberry for final approval while "The Cage" is being filmed in Culver City (there are images of Hunter and Roddenberry examining the model on this date). This model is used for all effects shots in "The Cage" except the most important one (the zoom in on the bridge).

- 24 Dec 1964 (Thursday): Shooting of "The Cage" wraps, only one effects shot still outstanding (all other model shots use the 33-inch model).

- 29 Dec 1964 (Tuesday): The 11-foot model (built by Datin, Mel Keys, and Vern Sion) was delivered to the Howard A. Anderson studio. This version is not powered and the windows are painted on the surface of the model. Even then the model was designed to be shot from the right side only.

- 23 Jan 1965 (Saturday): After "The Cage" is already in the can and waiting for network approval of the new series, additional test shots of the 11-foot model are taken in its original condition.

- 30 Jan 1965 (Saturday): Aspects of the ship's size (like it being 390,000 tons) were being distributed to the media in a promotion brochure (reprinted in Inside Star Trek: The Real Story as a separate section) describing the new show.

Recognizing her use for forced perspective shots, Anderson shot stock footage for use in the title sequence and future episodes. Besides "The Cage", the model would appear most notably in "Where No Man Has Gone Before", "Tomorrow is Yesterday", "By Any Other Name", and finally in "Requiem for Methuselah", ironically here as a desktop table model. In this last appearance, it could be discerned that the model had been damaged sometime earlier. Stills show that the hangar doors were missing, as well as some of the "intercoolers" on the rear top of the nacelles. In the episodes after the two pilots, the three-footer can be recognized by the fact that she, unlike her big sister, is not lit internally.

In August 1965 and April 1966, a series of revisions were made to the eleven-footer, of which the latter were mirrored onto the three-footer, except for the internal lighting and the animated nacelle domes, which were deemed too expensive. The model was stored away, after its final appearance in "Requiem for Methuselah."

After cancellation of TOS, the three-footer was given by the studio to Roddenberry, when he returned to the studio in 1975 in preparation for a second Star Trek series, and subsequently resided in his office for some years. Reportedly, he loaned the model to somebody during the early 1980s but later forgot to whom he had lent it, as was related to William S. McCullars' now defunct IDIC website by Majel Barrett-Roddenberry on 10 July 1997: "That particular ship was a real model and it was Gene's - he loaned it to someone and Gene forgot to get it back and it was never returned. It's a shame because it's a piece of stolen property and since it has historical value - it is quite priceless.".[4] The model has been missing ever since.

Eleven-foot model

Datin (l) takes delivery of the 11ft. studio model

The model

After the first review of the three-footer, Roddenberry green-lighted the construction of the large model, which would be exactly four times the size of the small model. Again, Richard Datin was entrusted with the job. This time, he was forced - due to time restraints and the limited size of his own workshop - to subcontract the bulk of the construction. The company he choose was Burbank-based Production Models Shop, owned and operated by Volmer Jensen. Most of the work would fall on his employees, Mel Keys and Vern Sion, closely supervised by Datin.

On constructing the "eleven-footer", Datin remembers: "The saucer section was constructed in two separate halves, top and bottom sections, of "Royalite" plastic sheet vacuum-formed over plaster molds, each representing the top half and bottom half of the saucer. The formed sheets in turn were supported, or held together, by a series of plywood ribs or struts radiating from the center. I have no idea how many ribs there were but a sufficient number to support the nearly one-eighth-inch thick sheet of Royalite. The plastic surface was thin enough to be slightly pressed inward with a finger. (...) At the point where the (solid wood) dorsal connected to the underside of the saucer, additional framework was added to strengthen the connection to the saucer. The dorsal was fastened to the saucer by one or two, most likely two, lag screws whose heads were set in below the top exterior surface of the the saucer. A small, low profile section made of wood hid the screws. The teardrop-shaped bridge section was made from a solid piece of wood with in its center hollowed out for installation of the hemispherical-shaped Plexiglas (bridge) dome (the same for the underside dome)...."

"The two engine nacelles consisted of a tapered frame constructed of plywood ribs fastened to the respective shaped solid wood ends," recalls Datin further. "The nacelle surfaces that faces each other were flat elongated areas of wood that were set in from the outer skin surface. Other details were added, such as what looked ans was described as wood shaped "handles", which Gene took an instant dislike at my terminology. But to me no better description fits! The rib frame was the covered with a heavy gauge pre-rolled sheet metal. A formed corrugated Plexiglas sheet covered the sides of the "S"-curved aft ends, while the forward domes were comprised of a semi-hard-wood-like ash and lathe-turned into hemispherical-shaped half domes. (...) The two support pylons were made of a solid one-piece hardwood, of either oak or walnut for strength." (Star Trek: Communicator, No.132, page 53)

The wooden secondary hull was subcontracted out, as well as several component pieces such as metal bits on the nacelles. The spikes on the forward nacelle domes were made by Datin himself. The same paint scheme as for the three-footer was applied, but no decals were used on this version; all the details on the hull - lettering, logos and all - were painted on. Virtually identical to her smaller sister, the eleven-footer lacked one detail. The surface on the backside of the aft nacelle caps was smooth, where the three-footer, as per specification, sported a detailed rectangular feature. Coming in at a length of 11ft, 2.08 inch and a weight of 225 pound, the model was delivered to Anderson on 29 December 1964. Too late for extensive use for "The Cage", the model was stored away for months while the studio pondered the fate of Star Trek.

Once the decision was made to have a second pilot produced, Roddenberry - with the people at Anderson's - decided to enliven the large model, in order to enhance their chances. Up until then, he had not wanted any of the models to be internally lit and they were delivered as such – shortly after, he changed his mind about that. Again, Richard Datin was called in to do the proposed revisions. Datin logged in another 88 hours of his work from 27 August through 8 September 1965, doing the following:

- Bridge: several painted-on windows removed, light panels added in front and on sides.

- Saucer top: nav lights added, black bands painted near port & starboard edge, painted black & white areas added near bow edge, four light panels added. The port & aft light panel was just painted-on and is not an actual light panel.

- Saucer rim: center-most bow port changed to nav light, some windows added.

- Saucer bottom: nav light & 2 portholes added near edge on each side, at 10 and 2 o'clock positions.

- Impulse engines: black rectangular vents painted over with hull color, eight small round black vents painted on.

- Secondary hull: strobe light added on aft flank, rearmost round porthole moved from left side of two rectangular ones to right side.

- Nacelles: black "grille" pattern painted on rear nacelle end caps.

- Registry markings were previously painted-on, now changed to decals.

The moment that Star Trek was to become a regular series, in early 1966, Roddenberry wanted to enliven the model even more, this time also retrofitted to the "three-footer". Yet again, Datin was called in to do the revisions, What he did was this:

- Bridge: bottom half chopped off, light panels removed, a red "beacon" added on each side. Some portholes added on B&C decks.

- Saucer top: black bands and most other painted-on markings removed, a round light panel added near bow edge, rib added on "linear accelerator" and both painted a darker gray.

- Saucer rim: Some portholes added, bow nav light replaced by light panel

- Saucer bottom: nav lights moved to 9 and 3 o'clock position, some portholes added, "nipple with phaser turret" added below sensor dome[5][6].

- Impulse engines: painted darker gray, round vents removed, original rectangular vents again painted black, texture wraps added on both ends of impulse deck.

- Dorsal: some windows/portholes moved/added, dorsal painted same as rest of hull instead of the earlier bluish reflective color, with a darker region on both leading & receding edge.

- Secondary hull: red "beacon" & green portholes added on top, some windows/portholes added, deflector dish diameter reduced, "observation booth" added under cowling above hangar bay doors, a grilled feature added on the center line just aft of the deflector dish housing and in front of the Starfleet-pennant.

- Nacelle pylons: four dark gray. brick-pattern inserts placed in slots.

- Nacelles: solid wood "power nodules" with spikes replaced with frosted Plexiglas domes with inner surface painted transparent orange, plus motorized vanes and blinking Christmas lights added behind the dome.[7] The original wooden domes are still in the possession of Richard Datin.

- Ribs and aluminum grille added in "trenches" along inboard flanks of nacelles and trench painted darker gray., patterned slabs added inside "intercooler loops" at rear, small slabs added in front of intercooler loops, black painted grille removed from end caps and light gray. spheres added.

- Typeface used for registry markings changed (resulting in that the number "l" changed to "1"), weathering added .

Datin worked an additional 419 hours on the second set of revisions from 8 April 1966 to 17 May 1966. Total costs for the "eleven-footer" (inclusive the retrofit revisions on the "three-footer" in excess over $6.000. The heavy internal wiring for the lighting pushed the weight of the model up to 275 pounds.

The port side of the model was not as detailed as the rest, especially on the secondary hull and the dorsal. The reason for this was that this side didn't need to be as, since here was the point located where the mounting rod was connected, this side would never be filmed. By far the vast majority of the shots seen of the "'eleven-footer" is the ship moving from left to right. On the very rare occasion that a port-side view was required (as in "Mirror, Mirror"), a visual trick was applied. Datin fabricated mirrored decals of the registry number on the nacelles and these were applied on the starboard nacelles. In post-production, the image would be flipped so that the number could be read as normal.

The second set of revisions are the ones also retrofitted onto the three-footer, save for the lighting options which were deemed too expensive. In this vane, the eleven-foot Enterprise model would be used for the rest of the series, save for minor revisions done at Anderson's during the run of the series:

- Upper sensor dome changed to a taller one, registry numbers on saucer bottom switched around so the starboard one was readable from a front view.

- Jeffries came up with a "deflector grid" which was drawn in pencil on the primary hull. It was drawn only to satisfy Roddenberry and was done very lightly so it wouldn't be visible on film.

Linwood G. Dunn shoots the 11-foot studio model

When the series went into production, it became obvious very early on in the first season that the special effects demands of a weekly production as complex as Star Trek (the most complex television production at the time) tasked the Howard Anderson Company beyond its capabilities. Three other SFX companies were brought in to ease the workload, The Westheimer Company, Van der Veer Photo Effects and Film Effects of Hollywood. The latter company, headed by Linwood G. Dunn, were sent the 3, and 11 foot models for additional filming of stock footage. "We received the 3-foot and the 14-foot [sic] models from Howard Anderson early in the first season. We had to make some repairs and modifications to the 14-foot model [rem: Dunn is referring to the may/april revisions of the 11-foot model] before we could begin shooting our effects.", Dunn recalled. (American Cinematographer, January 1992, page 39). Virtually all footage in the series, showing the Enterprise after the second set of revisions, including the interaction with the SS Botany Bay in "Space Seed", were shot at Dunn's company. Filming the model provided its own set of problems. As Howard Anderson Jr. noted, "We had to constantly stop shooting after a short while because the lights would heat up the ship. We'd turn the lights on and get our exposure levels and balance our arc lights to illuminate the main body of the ship and then we'd turn the ship's lights off until they cooled down. Then we'd turn them on and shoot some shots all in one pass. It wasn't until later that someone developed fiber optics and 'cold-lights' and other useful miniature lighting tools that are common today". (Cinefantastique, Vol.27, No.11/12, page 67)

After the series had been canceled, the eleven-footer was more or less forgotten by the studio and stored away in a far-away corner of the studio. The very fact that she was stored somewhere was a minor miracle because normal studio policy had it that, in those days, major set pieces of canceled shows or wrapped productions were to be demolished to make room for new productions. In April 1972, the model, minus its deflector dish was displayed at "Golden West College", Huntington Beach, California - arguably the very first time a studio model was on tour. While struggling to get the electronics back on-line, former Desilu employee (then employed at the college) Graig Thompson noted that the starboard nacelle interior dome rotated clockwise, while the port side rotated anti-clockwise. (Star Trek: Communicator, No.120, page 77)

One year later - in response to an inquiry from former Apollo astronaut Michael Collins - then-Paramount-executive Dick Lawrence responded, "I am pleased to advise you that Paramount Television will donate the 14 foot [sic] model of Star Trek's Enterprise to the Smithsonian Institution. It is my understanding that F.C. Durant III, assistant director of Astronautics of the Smithsonian Institution, in a letter dated December 17, 1973 to Mr. Frank Wright of our publicity department, has agreed to pay the cost of crating and shipping." (which was estimated at $350-$500, at the time) (Star Trek Giant Poster Book, No.10, 1977). The Smithsonian Institution received the model on 1 March 1974, in three separate boxes by Emery Air Freight and had it reassembled five days later for inspection. [8][9]

Apart from the already-missing deflector dish, the animated warp nacelle caps were also missing, by this time. F.C. Durant requested the following restorations, ultimately done by Rogay Inc.:

- Fabricate two hemisphere of Plexiglas (or other appropriate plastic) to replace missing pieces at forward end of propulsion units. Exterior surface of hemisphere to be "frosted" (sandblasted?). Interior surface to be painted with amber lacquer. Shade of paint to be approved by ASTRO. Affix hemispheres to propulsion units with small screws.

- At forward end of secondary hull, lay-out, fabricate and install missing "dish and spike" on "main sensor". "Dish" is turned from Plexiglas or other suitable material according to sketch supplied, Both dish and spike are painted bronze approximating existing paint on main sensor, Install using epoxy cement and original fitting.

- Replace missing Plexiglas rectangular and cylindrical "windows" in model. Attach other loose components including dome ("bridge") on top of primary hull.

- Retouch with black paint lettering on top of main hull, all black painted windows and other features, Fill two cracks on right dome on main hull with putty and retouch with matching paint, Retouch chafed damage and other minor injuries to reasonable point

- Push wiring inside or fold and affix on left side of model with three-inch silver colored, pressure-sensitive cloth tape.

This constituted the very first revision of the eleven-foot model - finished about three months later - and, while the restoration was generally well-received at the time, Durant couldn't refrain from commenting to Rogay about the nacelle caps. "The paint used by Rogay was turkey red, the exterior is not frosted as requested..." (Star Trek Giant Poster Book, No.10, 1977). The Enterprise was put on display for the first time at the NASM, the most-visited museum in the world, during the summer of 1974 in the Gallery 107 "Life in the Universe" exhibition. At the end of the summer of 1979, this exhibit closed and the miniature was moved to Gallery 113, "Rocketry and Spaceflight."[10]

Between 8 August and 11 September 1984, a second restoration was performed on the model in preparation for The Art of Robert McCall Exhibition. More extensive renovation occurred, this time - including removal of the silver-cloth tape on the left, unadorned side of the ship (where the internal wiring was hidden). In its place, the renovators added molded air-tubing, which covered the holes on the ship previously masked by the cloth tape. Internal lighting was improved and many of the lights that had not previously been working were made to work again. All internal wiring within reach (when the miniature was disassembled) was replaced. Additionally, spinning lights inside the engine nacelle hemisphere tips were added (although they remained painted the wrong color of red). The model was given a thorough cleaning, paint was retouched in several places, and several of the external decals were replaced at this time. With the refit completed, the Enterprise was unveiled at The Art of Robert McCall Exhibition, in September 1984, at the NASM's Gallery 211, "Flight and the Arts." After the McCall exhibition ended in September 1985, the USS Enterprise miniature returned to her former home in Gallery 113. (Template:Brokenlink)

A third, very comprehensive restoration was undertaken between 10 December 1991 and 24 January 1992, in preparation for the Star Trek Smithsonian Exhibit. Ed Miarecki was contracted by the museum to do the renovation. As he recalls on "The IDIC Page," "Basically, it was 'Being in the right place at the right time'. I had a chance meeting with Ken Isbell from NASM. He presented a slide show at a Star Trek convention in Baltimore. We had a nice dinner conversation and talked about the 'E'. He mentioned the state of disrepair the model was in and how the museum was considering refurbishment for the 25th anniversary exhibit. I made the comment, 'I wouldn't mind helping out with that.' He responded, 'Really'? We then spent the rest of the evening discussing details while watching a costume contest. When I got home, I submitted a proposal to NASM, and the rest, as they say, is history. (...) I was able, through the courtesy of several collectors, to acquire very clear B&W and color photos of the 'E' for my research. Also, one friend of mine had episodes on laser disc that we were able to 'freeze frame.' The model itself provided the most information about how it 'looked', however." Two of the most noticeable improvements were the replacements of the deflector dish by a more detailed one and the the "turkey red" nacelle domes with animated ones, approximating their appearance in the original series. The model was disassembled and each component was given a thorough refurbishment.[11] It was also decided to let the less-detailed port side of the model remain that way.

The most striking refurbishment was the new paint scheme applied. With the exception of the dorsal side of the saucer section (the museum requested this part to remain untouched, since its paint scheme was relatively in good shape), the model was stripped and repainted. The new paint scheme is noteworthy for its emphasized grid-lining (especially on the ventral side of the saucer) and weathering. "I have taken pictures of the 'E' after restoration under full studio lighting, (which does wash out most of the shading), and it looks exactly right. I hope you understand that the model will never look the way it did 30+ years ago because it was repainted in 1974 without first documenting its original condition. This 'interpretation' was our best educated 'guess'. If someone has better resources and expertise, they may have a chance to restore the model for the 50th anniversary," Miarecki elaborated further. Miarecki apparently was misinformed about the paint job at the time; no repaint was undertaken at the time, only retouching. Miarecki was required by the Smithonian to meticulously record his work in a log and have it videotaped. His team consisted of Steve Horch, Mike Spaw, David Hirsch, Tom Hudson, Ken Isbell, David Heilman and Roger Sides.

Miarecki's statement notwithstanding, the new paint scheme stirred up some controversy. As the original builder, Richard Datin, put it, "The original model was smooth and didn't show any lines or marks, except for the lettering and numbers (...) The Smithsonian had scribed lines to indicate panels, changing the character of the whole model." (Cinefantastique, Vol.27, No.11/12, page 68) The paint scheme is the main point of criticism and is hotly debated on blogs like "TrekBBS", "Resin Illumanati", "HobbyTalk", "Trek Prop Zone" and the museum blog itself. [12] The continuing criticism has somewhat alienated Miarecki from the fan base, as his reaction to a particularly strong comment on the "Trek Prop Zone" blog on 25 April 2007, showed. "(...) When I first started to read this topic, I had thought I was going to read something interesting. I really didn't expect my work to be described as "BUTCHERY". It has been now over 15 years since I performed the restoration, (without the aid of all the knowledge that has been acquired in those 15 years), and I have to endure in all that time since , nothing but jabs and barbs of criticism from over-opinionated fans who now have access to that knowledge. I have yet to read one compliment... any compliment, on any forum, about any aspect of my restoration. Now after all this time, I refuse to let such a "drive-by" insult such as yours go unanswered (...)"

The renovated, powered-up model featured prominently in the 1992-1993 Star Trek Smithsonian Exhibit and was, a year later, on loan to the Hayden Planetarium, New York City, for its 1993-1994 exhibition. Upon its return to the Smithsonian, the model would not be displayed for the next six years. In January 2000, the museum opened its new refurbished three-story gift shop. Part of the refurbishment was the permanent placement of the (unpowered) model, in a glass display case on the lower level of the shop, in March 2000. The model, reportedly insured at $1,000,000, is currently still residing there.[13]

Three- and four-inch models

As Howard A. Anderson, Jr. of Howard Anderson Company remembers, "In "The Corbomite Maneuver" we used a tiny four-inch model made by Matt Jefferies of the Enterprise to use in front of the huge alien ship to make it look even bigger. We also had an occasion to shoot Datin's three-foot Enterprise model from time to time and we used all three models in the main title sequence. We shot a lot of library footage using that little four-inch model but I can't remember any specific episode titles where it was used. We mostly used the 12-foot model." (Cinefantastique, Vol.27, No.11/12, p.67) It is, however, likely that Anderson (who, after all, made the comment almost three decades after the footage was shot) was mistaken about its filming usages after the title sequence. Analysis of screen captures show that the model used in "The Corbomite Maneuver" sported a lighted, lower sensor dome and running lights, identifying it as the 11-foot model, the only model outfitted with an internal lighting system. [14] There is no indication that the four-inch model (which may or may not be the balsa, wooden approval model that Jefferies built for the producers) was ever used again, after usage for the original title sequence.

The three-inch metal model of the USS Enterprise ...pulled in by the planet killer The in lucite encased three-inch metal model |

In the pre-production stage of season two, Jefferies designed a prop that he referred to as the "Enterprise working prop." It was to become the metallic three-inch Enterprise voodoo charm used in the upcoming episode "Catspaw". The design sheet, which was signed off on by Steve Sardanis, on 18 April 1967, specifically called for two pieces, one of which was to be encased in lucite. (IDIC Page website) Both pieces were used in the episode. The lucite-encased model was donated by Matt Jefferies, hand-delivered by Dorothy Fontana to the Smithsonian Institution on 7 November 1973, together with the original Template:ShipClass studio model. (Star Trek Giant Poster Book, No.10, January 1977) It was displayed only once, during the 1992-1993 Star Trek Smithsonian Exhibit. The other model (painted, this time) was later used as the Enterprise in the forced-perspective scene of "The Doomsday Machine", in which the ship is pulled in by the planet killer. This model's current whereabouts are unknown.

AMT models

AMT/Ertl's USS Constellation en route to its doom John Jefferies AMT/Ertl model ...in action in "The Trouble with Tribbles" Wesley Crusher's desktop model |

"At a point, Matt Jefferies called me about building a second three-foot model but they wanted it sooner than I could build it, so that second model never got built," Datin remembers. (Cinefantastique, Vol.27, No. 11/12, p. 67) What Jefferies had in mind was the upcoming episode "The Doomsday Machine", the very first time the Enterprise had to share screen time with a sister ship, the USS Constellation. The script required shots where both ships would be seen drawn in by the planet killer. To do this Jefferies and Anderson needed a second model in a appropriate scale in order to keep proportions believable on screen. Although Datin could not deliver, Jefferies had an alternative by this time. Instead of having had an expensive custom made model built, two of the then recently released AMT/Ertl Star Trek model kits (Kit nr. S921) were used. Fortunately as chance would have it they were supplied with a crude internal lighting option. One was distressed, its decals rearranged to read "NCC 1017", to appear as the battle damaged Constellation. The Constellation model was most likely discarded after use (although footage of this model was to be reused to represent the USS Excalibur in "The Ultimate Computer"), The second model was used as the Enterprise in "The Trouble with Tribbles" as a background model seen in Lurry's office window and orbiting the far side of Deep Space Station K-7. In the auction description, mentioned hereafter, a former member of the production crew remarked that the modified interior lighting system proved to be problematic in that the operation of the animated nacelle domes was very noisy and had to be painstakingly edited out in post-production. The model was a short time later on loan to GAF Corporation, alongside the 3-foot model for a fotoshoot for their view-master version of "The Omega Glory", representing the USS Exeter. It was in the possession of Matt Jefferies' brother John until 2001, when it was sold to Microsoft's co-founder Paul Allen in the Star Trek Profiles in History Auction, on 12 December 2001 at a price of $42,500 [15][16] and is currently residing at his Science Fiction Museum and Hall of Fame in Seattle.[17]

An AMT model, built by Ronald D. Moore when he was 12 years of age was seen as set dressing in Kirk's quarters in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country as was revealed in Michael Okuda's text commentary of Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (Special Edition) dvd.

In TNG: "The First Duty" a desk top model of a original Constitution-class ship could be seen in Wesley Crusher's dorm room. This was an unmodified 10 inch pewter model released by Franklin Mint in 1988, model 810, of the Enterprise.

Another AMT model kit (No.8790) also wound up on screen in Star Trek: First Contact as one of the golden models in the display case in the observation lounge."This was before eBay, so I went and scoured the hobby shops all the way from Los Angeles to PHX Arizona to find any and all kits of the Enterprises. What was available then was the Enterprise A, a TOS Enterprise that was too small so I opted to get the cutaway version that was substantially bigger, and the Ent. D.(...) Herman asked for 3 of each ship because we were now going to have the smashing of the case scene.", Eaves remembers on his blog.[18] Molds were taken of the model and solid resin casts copies were made (since there were multiple takes of the scene). After smoothing out the surfaces, the models were gold plated at ArtCraft Plating. The models were subsequently smashed when the scene was filmed. For Star Trek: Insurrection there were again three models needed, this time because there were three display cases and Eaves more or less repeated the procedure, solidifying the models by filling them up with resin. They were seen as display models in the observation lounge.[19]

Eaves and the studio retained most of the models but some of them were sold at auctions. One was sold in April 2007 in It's A Wrap! sale and auction for $1,411. [20] to American collector Jason Stevens[21]and another one has reportedly been sold in an on-line Sotheby's auction in October 2000.[22]

Trials and Tribble-ations model

The Jein model ready for shooting at Image G

For Deep Space Nine's "Trials and Tribble-ations" episode, Gregory Jein (who is a lifelong fan of the original series), in ten days, faithfully recreated a 5.5-foot physical model of the USS Enterprise.[23] Jein was delivering the new USS Excelsior-model for Voyager's "Flashback" episode when he caught a glimpse of Gary Hutzel's test footage. He recalls being informed, "Yeah, we'll probably do a model of the "Enterprise" but we don't know when, and we probably won't till the last minute (...) being a crazy kind of guy, I decided to start work on it anyway!" (Star Trek: Deep Space Nine Companion, page 386) and,"It was a sort of a lark, it takes awhile to get the paperwork and budgetting done, and if I had waited for them we never would have time to do it. So, I really started it myself." (Star Trek: Communicator, issue 110, page 63). He based his model on carefully-taken measurements taken of the original eleven-foot model by Gary Kerr when it was disassembled at Miarecki's shop for its 1991 restoration. Back then Kerr took pictures and measurements for his own personal edification. When his friend Jein mentioned to him five years later that he needed blueprints for the recreation, Kerr was able to to tell him that he could provide them. "I got all my measurements together, and every night after work I'd sit down at the drafting board. Greg needed the basic shapes of the saucer, the engines, and the hull. I'd draw some plans, go to Kinko's to make copies and send them all off to him, and the I'd go back to the drawing board.", Kerr remembered (The Magic of Tribbles: The Making of Trials and Tribble-ations, page 36). Additional and missing measurements Kerr obtained from Miarecki, who had maintained a log on his restoration, though he could provide them only at the last moment since he was working on the studio model of the Enterprise-E at that moment. On the construction of the model Jein noted:

There were four different components to build. The saucers were all turned by Gunnar Ferdinandsen, a plasterer and foammaker. They were spun out of plaster on a template, just like throwing a pot, and then we vacuformed those patterns and detailed them out, and then we made silicone molds of them. The main engineering hull, the pylons, and the the engine nacelles were all made out of wood. Thet were turned on a lathe, and then we detailed those out and made silicone molds of them." From these molds the final plastic parts with which to assemble the model were cast. With Larry Albright Jein continued on the lighting,"We put banks of neon behind the windows for the interior of the saucer and the main engineering hull and of course we have strobe running lights on the saucer, like on the original. The only parts we didn't do were the spinning lights on the caps of the nacelles. Gary Hutzel designed those.(The Magic of Tribbles: The Making of Trials and Tribble-ations, page 37-39)

Hutzel had to take into account that unlike the original series where the model was shot in real time, that models were now photographed in motion control. He had to create a computer program to control the light effects to match the different frame rates. Building the nacelles presented another problem. By season two of the original series the aft of the nacelles sported spheres, but in the "The Trouble with Tribbles"-episode stock footage was used from the pilots were the aft sported louvers. Which version to use? Hutzel recalled,"Í asked Michael Okuda what he thought the fans would say. He said that no matter what the stock shots were, the fans would know it's not supposed to be louvers. So I called Greg back to tell him to go ahead and do the spheres. And Greg said,"That's okay, I already made them both. I wasn't going to wait for you to make your make up your mind!"."(The Magic of Tribbles: The Making of Trials and Tribble-ations, page 40-41) Painting the model in the correct color, "Federation Gray" as Jein called it, proved easier than could be expected. Back in 1991, Miarecki had a piece of the original paint computer analyzed by a specialized paint store which came up with an exact match for the shade of gray that turned out to be a 1964 General Motors car colour-GM gray 4539L (Sci-Fi & Fantasy Models, Issue 14, page 28 and which somewhat contradicts Miarecki's own earlier statement to the IDIC-page). The only snag was that the formula was lacquer-based which was prohibited in California, so an environmentally friendly formula had to be developed first. Jein opted to include some of the modifications both Jefferies (the grids on the upper saucer section) and Miarecki (grids on the bottom saucer section amongst others) had done on the eleven-footer. This was done in a far more subtle way than the 1991 restoration as not to distract from the perception people had of the Enterprise in her original appearances. Unlike her progenitor this model was outfitted with several more mounting rod points, so that the model could be shot from several different angles. When delivered, the model weighed in at 40 pounds. A limited production run of twelve pieces was made from the same molds used for this model and were sold at Viacom Entertainment Store in Chicago for $10,000 each in 1997, accompanied with a certificate signed by Jein and Jefferies, one of which resides at Paul Allen's Science Fiction Museum and Hall of Fame in Seattle.[24]

CG models

For the Enterprise episodes "In a Mirror, Darkly" and "In a Mirror, Darkly, Part II" a CGI model was built of the USS Defiant. The model was built by Koji Kuramura and mapped and animated by Robert Bonchune at Eden FX. Remapped to represent the USS Enterprise, it would also appear in the final scene of "These Are the Voyages...".[25][26] While the model was under construction, Bonchune commented on the HobbyTalk blog on 18 March 2005,"There is some subtle "aztec" paneling and some slightly heavier weathering. We also do have subtle deflector grids on the ship. Some of these additions were requested by the producers. We also have an enormous time crunch, so if it ain't perfect, trust me, we know....The CG ship was wholly and ENTIRELY built from scratch by Koji Kuramura, Nacelle effect by me with reference help from Thom Sasser as well as just looking (over and over and over and over....ad nauseum) at clips from the Orig show. Any ship dimensional reference material we needed was provided by Doug Drexler as well as Koji's own research. I know Doug is good friends with Gary Kerr, so I am sure that made it's way to us through him. As for the Petri [Blomqvist] help, Koji used his shape for the back end of the nacelle cap as a reference piece. We needed it built differently.".[27] The script called for aft firing weaponry, something that up until then was not shown for the original Constitution. Bonchune remarked,"(...)the intention was that the rear torpedoes were from the little round port right between the impulses engines. We tried to make it logical with what existed so we didn't have to make a new hole on the ship. Everyone agreed, except that apparently if you frame by frame it, they actually come from the hangar bay phaser mounts. Someone in the chain either decided against it or didn't know. Even one of the writers was surprised it hadn't been done as discussed."[28]

A second CGI model was built for TOS remastered. Although several parties made pitches to do the model, like Digital Stream, Daren Dochterman [29], and Eden FX (that model being built by Pierre Drolet[30][31][32]), CBS Studios decided to go in-house with their own company CBS Digital where the model was built under supervision of Niel Wray and David Rossi, based on the same meticulously taken measurements of the original model for the Jein model. Of particular concern to producer Michael Okuda was that the model was not too realistic looking as to keep in line with the overall look of the series. The model had to be remapped after a couple of episodes, because it was looking too detailed. A particular advantage was the increased number of angles the ship could be shown in. "In the original series you only see it in 17 poses, we are going to give you 50 or 60,", Rossi explains.[33]

The models built by Dochterman and Drolet found their way in the Star Trek: Ships of the Line calendars.[34][35]

Designing an Enterprise that never was

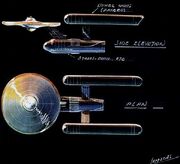

Early ads for The Motion Picture portrayed the upgraded Enterprise initially designed for Phase II by Jefferies

A Ralph McQuarrie Enterprise concept art, ultimately rejected in favor of Jefferies' design

Ralph McQuarrie, best known to the public for his stunning production designs for the Star Wars films, was hired by Ken Adam to help develop the designs for the new Star Trek: Planet of the Titans movie, ultimately abandoned to make way for Star Trek: Phase II, the new television series. Although the design used the same elements as the original design, saucer shaped primary hull, warp engine assemblies and a engineering secondary hull, the secondary hull was flattened and wedge shaped, providing a radically different look, one not unlike the Star Destroyers McQuarrie designed for those films.

Their Enterprise design, however, was abandoned, and Roddenberry asked Matt Jefferies to update the famous starship to reflect the refit that would be part of the Phase II-series' back story. Jefferies' redesign changed the engine nacelles from tubes to thin, flat-sided modules, and tapered their supports. He also added the distinctive photon torpedo ports on the saucer connector.

"Basically," Jefferies said, "what I did to it was change the power units, and make a slight change in the struts that supported them. I gave the main hull a taper, then I went flat-sided and thin with the power units, rather than keeping the cylindrical shape. Trying to work out the logic of the refit, I knew a lot of the equipment inside would change, but I didn't see that there would be any need to change the exterior of the saucer. Certainly, though, the engines would be a primary thing to change. Part of the theory of the ship's design in the first place was that we didn't know what these powerful things were or how devastating it would be if anything went awry, so that's why we kept them away from the crew. And that meant they could be easily changed if you had to replace one." (Star Trek Phase II: The Lost Series, page 27) Jefferies started work from drawings he'd actually prepared for the original series that showed the Enterprise with flattened nacelles, to be presented to Roddenberry if he did not like the first version.

Unlike the first redesign of the Enterprise, Jefferies' new version, further detailed by Mike Minor and Joe Jennings, was designed along the classical lines of the original albeit modernized. But when Paramount Pictures abandoned its plans to create a fourth television network and subsequently transformed the second Star Trek series into the first movie, that Enterprise, already in the process of being built, was discarded as movie director Robert Wise brought in a new art director – Richard Taylor – who assigned Andrew Probert to do a second redesign of the ship, essentially keeping with Jefferies' new lines, while adding the extensive detail that was necessary for a motion-picture miniature.

"Planet of the Titans" models

...in Earth Spacedock ...at Surplus Depot Z15 (bottom) |

Based on Ralph McQuarrie's design of a new Enterprise for the proposed Star Trek: Planet of the Titans movie project, at least two study models were build, before the project was canceled. Stored away for the better part of a decade the models would make a surprising reappearance. Although stated as having made an appearance in the debris field of "The Best of Both Worlds, Part II" (The Art of Star Trek, page 56), they have not been identified as being there.[36]

One of the models, however, was present as B-24-CLN at the Surplus Depot Z15 in TNG: "Unification I". Part of the other model could be seen in Star Trek III: The Search for Spock docked in Earth Spacedock when the Enterprise enters. The models therefore became canon albeit without class designations or names.

"Phase II" model

Brick Price's unfinished Star Trek: Phase II studio model of the USS Enterprise

After Matt Jefferies' redesign was approved for the Star Trek: Phase II television project in 1977, detailed construction blueprints were drawn up for construction of the physical studio model[37] (which were not the ones published in Star Trek Phase II: The Lost Series, color section). To ease the workload, Magicam hired Brick Price's Movie Miniatures to build the master model. Price brought in modeler Don Loos to do the bulk of the construction work. Work on the four-foot model was in progress when the project was upgraded to the Star Trek: The Motion Picture movie project.[38]. "I did the new working drawings with my board on the bed in a hotel in Tuscon, because we were on location with Little House. I came back and had them printed. Don Loos had the engine pods finished, and was working on the struts, but around that time I had to quit.", Jefferies remembered (Star Trek: The Magazine Volume 3, Issue 12, page 85}. Both Robert Wise and Richard Taylor decided that the model was too small and not detailed enough to meet big screen requirements and a new model had to be build from scratch. Price was pulled off the project in January 1978 (though his company would remain to build props for the movie) and the task of building a new model reverted back to Magicam.

The fate of the unfinished model (built out of fiberglass with joint connections made of undersized aluminum sheet plates and therefore, despite its size, quite heavy) is somewhat unclear. Although unsubstantiated it is possible that Price finished the model years later for "The Planet Hollywood" restaurant in New York City in the early 1990s. The saucer section and torpedo launchers were heavily adjusted to reflect the appearance the refit Enterprise has in the movies. The nacelles, secondary hull and the upper dorsal retained its original Phase II design, resulting in an unfamiliar looking hybrid between the Phase II and the movie's Enterprise.[39] Star Trek aficionado William S. McCullars has maintained on his now defunct website "The Idic Page" that it was indeed the original studio model, showcasing pictures provided by Price himself. The model has been on display in the restaurant during the 1990s.

Although this particular design has not become canon, the design has captured the imagination of fans. Daren Dochterman built a CG model that will be used in the fan film production Star Trek: New Voyages (now known as Star Trek: Phase II) in their upcoming episode "Enemy: Starfleet".[40]

Designing a Motion Picture Enterprise

For Star Trek: The Motion Picture, the new Enterprise was re-designed by Andrew Probert, based upon Minor's and Jennings's concepts for Phase II. Other artists who worked on the refit design were , Douglas Trumbull, Harold Michelson and Richard Taylor himself. As art director Taylor felt, after prodding from Roddenberry, that they should stay with the proportions inherited from Jefferies' upgraded Enterprise for Star Trek: Phase II, Probert lengthened the ship with merely a few feet and enlarged the saucer, eventually adding an updated superstructure to the top and bottom of it. Additionally, he came up with the new photon torpedo launcher, redesigned the whole navigational deflector dish area, updated the impulse engine, and added phaser banks around the ship while Taylor took upon himself to re-design the warp nacelles.

Eight-foot motion pictures model

Originally art director Richard Taylor wanted to totally redesign the Enterprise from scratch, once the movie project became definitive in December 1977, but Roddenberry vetoed that notion and insisted to keep the basic design as established for the Phase II project and instead to concentrate on redesigning the details. (Star Trek: The Magazine Volume 2, Issue 8, Page 85.) Roddenberry's veto enabled Magicam's Jim Dow and his crew to start construction on the model in the spring of 1978. Dow and co. started with constructing an aluminum framework for internal strength for the model and as a armature for mounting the finished model for filming. Since no story-boards were yet available at the time Dow had the foresight to equip the frame with five mounting points for 360 degrees shooting options around its center of gravity (though the top mounting point would be eliminated later in the process).(American Cinematographer, February 1980, pages 152-155 and 178-180) Plastic vacuum-formed molds were subsequently applied to the frame to skin the model. Redesigned elements from Taylor and Probert were built and applied as they came in during the construction of the model, making the redesign a process on the fly. As a result detailed blue prints of the model could only be drawn up after the model was finished by David A. Kimble.

For internal lighting, Dow decided to use neon. "Almost all the cabin portholes are neon - neon because the model had to be sealed, and neon has the longest life and generates the least amount of heat. It was next to impossible to provide maintenance ports in the Enterprise because it's such a smooth-skinned object. We didn't have the luxury of all that nerny detail that the Star Wars models had, to hide the lines of panel openings. But now they've added so much skin detail - which I'm sorry to see esthetically - that we could have done it. Our job would have been much easier: we could have opened it up for access to the lights and wiring.", Dow later remembered. (Starlog, No.27, October 1979, page 29) The inaccessability of the internal wiring would bedevil SFX-crews in later movies. Dow and his team finished up on the model in September/October 1978 and delivered it to the producers, coming in at 70 pounds. At Trumball's insistence however, further detailing and revision of the lighting, meant that work on the model continued in the months that followed.

While construction on the model was still in progress, Zuzana Swansea designed the surfacing detail for the saucer section, most notably what was to become the Aztec pattern (a hallmark for later classes of Federation star ships), however she lacked the painting skills to apply these details herself. In order to accomplish this, Dow contracted free-lance airbrush artist Paul Olsen early on to apply the paint job. Working on the model, starting with the dish, for the better part of eight months, the most striking part of his work was the application of a high gloss pearlescent lacquer coating which gave the Enterprise a chameleon-like appearance in the movie, changing its color appearance depending on the kind and direction of lighting. The Aztec pattern for example would be only visible if the light hit the model at an oblique angle ("I used four pearl colors that were transparent: a blue, a gold, a red, and a green...they all flip-flopped to their complements when the viewing angle changed. Beautiful. By varying the amount of color, and the mixture of several colors on top of each other, I obtained myriad colors and depth of color.", Olsen would later remember.[41]) Though considered magnificent, the paint job would cause some trouble for Douglas Trumball in shooting the model. As Olsen remembers on his website, "Dear old Doug drew me aside with one of his big grins and said, "Paul, it's terrific, but we may have problems shooting it because I think we'll get light kicks off the edges of the model." The model was so bright and so colorful that light flare against the black background she would be shot against would make it impossible to isolate the edges of the model from the background so a star field or planet fall or other effect could be photographically dropped (matted) in cleanly. They would have to shoot the model with low light, which would cool the reflections and all the model detail as well. There are still some shots where the opalescence can be seen, but the real thing looked so much better than can be seen in the movie."[42] Olsen was assisted by Magicam's Ron Gress, who worked on the secondary hull.

Trumball, who did not use the traditional technique of bluescreen miniature photography managed to work around the problem. "(...) We shot all the the Enterprise footage because the Enterprise had a white, shiny surface and would have caused tremendous matting problems at Apogee. Spill light from the blue screen would have reflected off the ship and created holes in the mattes. Even with our high-con operation we had quite a problem pulling decent mattes off that model: with blue screen it would have been nearly impossible." (Cinefex, No.1, 1980, pages 12-14). Trumball also had the internal lighting rewired to satisfy his vision of a concept of self-illumination as opposed to a model completely awash in light as it was originally constructed.

The model, including the revisions Trumball requested, pushing the weight up to 85 pounds, took in total 14 months to complete. Measuring 100x46,5x21 inches she reportedly was constructed at a cost of $150,000. (The Making of Star Trek: The Motion Picture, page 207)

Dow and his team made the model a rugged one, suspecting the model would be used in in subsequent outings. His foresight was fortuitous since it became apparent that The Motion Picture would have follow-ups. The model, being constructed out of molded plastics instead of the heavier fiberglass traditionally used until that time, was considered light at the time. By 1981 however that view was not shared by the SFX team of Industrial Light & Magic, who was handed over the model for pre-production of Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. Although admired, the model was soon loathed by the team for its cumbersome handling and heavy weight. Director of photography Kenneth Ralston has been on record for his open dislike of the model at the time, "I hate that model. I think it's made out of lead. I don't know what's inside to make it so heavy; it took eight guys to mount it for a shot and a forklift to move it around." (Cinefantastique, Vol.12, No.5/6, page 54) and, "I hate that ship. I've said it a hundred times, but it's true. I think it's ugly – the most silly looking thing. The model is murder to work with, so I'm glad it's gone," he recalled while preparing the Enterprise for destruction in Star Trek III: The Search for Spock. (American Cinematographer, August/September 1984, page 61) The cumbersomeness was part of the reasons why the class of the USS Reliant was redesigned from a Constitution-class (as it was originally envisioned in an early draft of the script) to the Template:ShipClass (the other reason being that the producers were afraid that audiences would not be able to tell the two ships apart during the battle sequences). (Star Trek: The Magazine Volume 3, Issue 3, page 83)

Further problems arose with the internal wiring for lighting when some of the lighting shorted out. Unable to procure help from the original electricians from Trumball's company EEG (Trumball also tendered a bid to do the SFX for the movie, but was passed over in favor of ILM), Martin Brenneis, responsible at ILM for all the electronics and supervising model maker Steve Gawley had to figure out for themselves how to fix the problem. As Brenneis recalls, "The lighting in it was obviously done by a model maker who knew nothing about electricity. I and a couple of the model makers had to do some rewiring to least make it safe! It was too much work to completely rewire it, but we patched the bits that really were hazardous so that we could use it. Another complication was that all the lights were sealed inside the ship, so if even one was damaged the entire model would have to be taken apart.". (Star Trek: The Magazine Volume 3, Issue 3, page 20)

Using the bluescreen miniature photography technique, Ralston soon encountered the same problems Trumball had with the intricate paint job whilst shooting. Because of budget restraints not being able to change filming techniques a decision was made to give the model its first repaint. Highlighting details with matte paint on the hull and using dulling spray, the team got rid of the pearlescent gloss of the model. However since in the movie stock footage of The Motion Picture was also used, the Enterprise appeared in The Wrath of Khan in both liveries.

Although Trumball liked the model of the Enterprise he initially considered the model too small for his purposes, or as he stated it, "the Enterprise in particular, was one-fourth a big as it should have been. Even in Silent Running, which was a low budget movie, our space craft was twenty-six feet long; In 2001, the Discovery spacecraft was fifty-four feet long. But in Star Trek, the Enterprise is barely seven feet long; and it was just an enormous struggle to get not only a sufficient degree of detail, but also camera angles and depth of field and lighting that worked." (Cinefex, No.1, 1980, page 15) Ralston came to agree with Trumball, when it came to shooting the scene where the Enterprise is hit by Reliant's phaser volley. In order to get the detailed close-ups (and in order not to have the master model damaged), Gawley and his team build an enlarged section of the forward upper secondary hull with the dorsal. The model, measuring 48x24x27 inches, was constructed out of wood and skinned in wax so that simulated damage could be easily sculpted on the surface but could also be easily reversed if the need arose as it eventually would in Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, and Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, the three other movies the section model would be used in.

The section model, known as Lot #992, being part of the 40 Years of Star Trek: The Collection auction, estimated at $1,000-$1,500, was eventually sold on 7 October 2006 with a winning bid of US$9,500 (US$11,400 including buyer's premium) to American collector Adam Schneider.[43]

For The Search for Spock, the intricate self-destruct sequence required additional enlarged sections of the Enterprise model, a close-up model of the bridge and two close-up models of the upper saucer section. As Ralston recalls,

(...) my involvement began at the top of the bridge when you see it blowing up. It was a miniature that we shot with the Bruce Hill camera. Sean Casey had done a lot of the work on all those models, mold-making and things, because we had to do a lot of tests before we ever got to really shooting it. The pyro work was headed up by Ted Moehnke, who did a great job on the show. I think we got some nice pyrotechnics and different pyrotechnics, too. So it was a full miniature blown upo. Then we had to pull a matte of that put some stars in because it was just shot against black. Then we cut back to the Bird of Prey ship moving away from the Enterprise and dropping down. The top is blowing up. What we did &nash; Don Dow shot that one – we just painted out the top with black. If it's against the stars, you won't be able to see it... We painted it real black. We weren't about to destroy that $150,000 model that Doug Trumball [sic] built. I was tempted though-tempted many times to take a mallet to it. Anyway, we had a projector and we were projecting the explosion going off on top of the ship. What you are seeing isn't the ship moving. The camera system is doing all those moves with the ship and all the different light passes. Then we come back and shut off all the lights. We project the the explosions on the ship and repeat the same moves with explosions going off. It looks like it's all locked into the same element. We also put light effects on top of the ship. Next we cut to the famous number (NCC 1701) being eaten away and the explosions going off. Bill George devised a very light styrofoam that he laid over this incredible grid work-something he came up with in 20 minutes or so. It looked great. We dripped acetone or MEK or something really vile stuff on the surface, but you can't see the stuff dripping on it. I wasn't sure it would work. The camera is shooting over a frame a second, that is why it is hard to see the drip. We had to get all the light off it, too, or you would see a light coming down. The grid work was shot separately from the surface. It was all put together later so we could do light effects. And some of the explosions were just Ken Smith, the optical photography supervisor, burning out certain frames. Then the ship comes right up to camera and the whole dish blows off. Again, the ship wa shot using all the same techniques-projection on the surface, etc. But the final explosion, when the whole thing goes, is a large dish shape which Sean made out of plaster. I sprinkled talcum powder over it to get more fine material coming off it. It had several explosives inside that Ted had come up with. And we shot it as high speed as we could, It still wasn't as slow as I wanted it. The explosion was supered over the ship. There is also a stock explosion from The Empire Strikes Back in there too. It comes out from underneath the dish to make the explosion seem a little more cohesive and not so much of an effect.(American Cinematographer, August/September 1984, page 61)

The master model itself, virtually used back to back was not modified further for this movie aside from the application of battle damage, both in the form of paint and rubber patches, molded and painted to simulate battle damage. Aluminum slivers were also applied to simulate peeled back hull plating.

After the third movie, the continuation of the movie series was henceforth by no means an automatic certainty, let alone the reappearance of the Enterprise-model, so the model was not cleaned up and put away in storage. By the time Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home went into production and it became obvious that Kirk's new command would be a new Template:ShipClass ship, ILM's modelshop had to do a major refurbishment of the model, to make it appear as a new ship. By now the the damage add-ons had adhered to the paint and removing them caused damage to the paint, so a first true re-paint was necessary (though the original paint layer was not removed). The decals were also replaced to signify the new call sign "NCC-1701-A". Concerns existed about the internal lighting system, but it held up. It was in this finish that the model was originally slated to represent the USS Stargazer in the TNG: "The Battle" episode, before a last minute decision was made to introduce a new shipclass.

Another unexpected refurbishment was necessary in early 1989, when the model was uncrated at the New York based effects house Associates and Ferren. Fully expecting to be able to shoot the model at once for Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, Bran Ferren was dismayed when he observed that, "One entire side of the Enterprise model was sprayed matte gray, destroying the meticulous original paint job. We had to go in and fix it before we could shoot it, which took two painters and an assistant about six weeks to do." David V. Mei was the lead modeler responsible for the refurbishment which also included replacing the decals that were crumbling.(Reportedly, the vandalism was done by a film crew member of Universal Studios, when the model was on loan for a video presentation for one of their attractions, in order to work around the blue-spill problem). This time around the internal lighting did not work properly. "Also, the Enterprise turned out to be an electrical challenge that only continued to work because there were sufficient short circuits within it to keep it arcing into operation - so we had to rewire it", Ferren continued. (American Cinematographer, July 1989, page 83) The refurbishment was a serious set-back on an already very tight budget.

Two years later, the model was hauled out of storage once again for preparation for Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country and sent over to ILM's modelshop. Lengthy financial negotiations delayed start-up of production, but ILM made use of the time offered them to give the models sent to them a thorough overhaul. Although pleasantly surprised about the overall shape the model was in after more than a decade, the first thing art director Bill George and his team of modelers tackled head-on was the ever re-occurring headache, internal wiring. This time the model was opened up and the wiring was repaired and modernized. "The original powerbus was situated in such a way that about a dozen small wires had to be snaked individually through the different access ports. Jon Foreman went in and rewired the Enterprise with two specific goals in mind: one, make it easier to to mount by having a single harness to route through and connect up: two, since we wanted to cut down the number of passes required for each shot, the exposures for the various lights on the ship had to be much closer in intensity. Prior to this, the running lights, window lights and sensor dome had been shot with separate passes:: but by reworking the wiring, these could now be recorded in a single pass, thus reducing stage time.", George recollects.(Cinefex, No.49, page 42) Also the model began to show its age, now being covered with hairline cracks, damaging the paint layer and also Olsen's original pearlescent paint scheme starting to reassert itself yet again. The cracks were filled with putty and sanded down, a new paint layer was applied by Kim Smith together with layers of dulling spray.

For the scene where the primary hull of the Enterprise is pierced by a torpedo, an enlarged 8-foot saucer was built. "When Scott [Farrar] and I were in the very early design phases, trying to come up with ideas to make the battle a little bit different, he asked me, "What have you always wanted to see happen to the Enterprise?" and I my answer was, "I've always wanted to see a photon torpedo go right through the ship. There's one place on the primary hull where it's really thin." We designed that shot and they accepted it. We wanted to make sure that it didn't look as much like a explosion as a shotgun blast, because the photon torpedo's actually pushing through the ship. We built a huge eight-feet diameter dish with replaceable breakaway section made very of very fragile plaster, then hung the model upside-down. On the side away from the camera were fingers of metal that were dressed as the damaged ship. When a pin was pulled, a spring pushed them right through the plaster skin, which cracked since it's supposed to be ceramic tile.", George further recalled. (American Cinematographer, January 1992, page 61)

This proved to be the last time the model was to be used as a shooting model for a Star Trek production.

Shortly after wrapping up the production for The Undiscovered Country, the model went on tour, firstly to the 1992-1993 Star Trek Smithsonian Exhibit and a year later to the Hayden Planetarium, New York City, for its 1993-1994 exhibition in both instances shortly reunited with its progenitor.[44] In 2001, the model was sent over to Foundation Imaging as a reference guide for modelers Robert Bonchune and Lee Stringer for their CGI model they were building for 2001's Star Trek: The Motion Picture (The Director's Edition). On 1 November 2001, the model was on its last public display before being auctioned off in the lobby of the Paramount Theater for the Star Trek: The Motion Picture (The Director's Edition) Event, where the revamped movie was premiered.[45]

This model, known as Lot #1000, being part of the 40 Years of Star Trek: The Collection auction, estimated at $15,000-$25,000, was eventually sold on 7 October 2006 with a winning bid of US$240,000 (US$248,800 including buyer's premium). The model was featured in the documentary Star Trek: Beyond the Final Frontier, as the Okuda's uncrated the model. The model was acquired by Microsoft's co-founder Paul Allen for his Science Fiction Museum and Hall of Fame in Seattle, where it currently resides (although due to space restraints it is not on permanent display).

Twenty inch AMT models

Apogee's 1-foot model under construction ...and in action in Star Trek: The Motion Picture |

"There is also a second model of the Enterprise which is twenty inches long, used for long shots," Sackett/Roddenberry claim in their book The Making of Star Trek: The Motion Picture, page 207. It is the model John Dykstra refers to as the "one-foot" model,"But for some of the more distant shots we built and photographed a smaller version of the Enterprise, about a foot long."(Cinefex, No.2, 1980, page 67) Built specifically for forced perspective shots by Dykstra's Apogee modelshop, it was used for the passage of the Enterprise over V'Ger emphasizing the size of V'Ger (itself an eighty-six feet long studio model). To date only referenced to by Roddenberry and Dykstra, it is the least known of all the Constitution-class studio models, and nothing else about the model can be said with any certainty.

What is certain however, is that the model was never used again, since ILM, unaware of its existence, built a new smaller Enterprise model for Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, using a by then available AMT/Ertl-model kit, no.S970. "In fact we used one of the AMT kits to build this little model of the Enterprise, which has about a twelve inch diameter dome. We actually put lights in it and used it in instances where we had to be far away from the ship. With the big model, you can't get too far away and make it look far away – it always looks big. So we used that one for anything where we wanted the ship real small," Don Dow (brother of Magicam's Jim Dow) remembers. (Cinefex, No.18, 1984, page 63) Intricately detailed and lit by ILM, measuring 22 inches in length, the model would see use from Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan through Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, with the exception of Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home.

This model was sold as part of the 40 Years of Star Trek: The Collection auction, estimated at $15,000-$20,000, was sold on October 7, 2006 with a winning bid of US$40,000 (US$48,000 including buyer's premium). [46] In a run up to the auction, the model was on tour at the Creation Convention in Las Vegas from 17 August to 20 August 2006.[47]